Dubrovnik quarantine

During its fascinating history, Dubrovnik has been a city centuries ahead of its time when it came to public health. Back when much of Europe struggled with basic sanitation and unregulated cities, the Republic of Ragusa had already set up structured health policies and strict hygiene laws. Dubrovnik quarantine was in fact one of the first quarantine systems in the world.

The word “quarantine” may be common now, but few people realize it has roots right in this city. Dubrovnik’s leaders were practical and dedicated to keeping the population safe. All that without closing off trade or isolating the city from the world.

When we look at the organized quarantine stations, early hospitals and sewage systems that Dubrovnik had in place at the time, we can see this system was planned, regulated, and efficient. These public health strategies were long-term policies built into the fabric of how the city worked. If you’re visiting Dubrovnik, it’s worth exploring the places that once helped shape modern health systems.

The origins of Dubrovnik quarantine

In the late 14th century, Dubrovnik, which was then known as the Republic of Ragusa, faced the same threat as many other Mediterranean ports. There was a spread of deadly diseases brought by travelers and merchants arriving from abroad. In order to protect its citizens while keeping trade routes open, the city introduced one of the first documented quarantine systems in the world.

The policy was officially established in 1377. Under this law, all newcomers, particularly those arriving from areas affected by plague, had to spend time in isolation before entering the city. The original period of isolation lasted 30 days and was carried out on uninhabited nearby islands such as Mrkan, Bobara, and Supetar, just off the coast from Cavtat. In this way the authorities could separate visitors from the city population while still providing access for supply delivery and medical inspection.

Over time, the isolation period was extended to 40 days. This led to the creation of the word “quarantine”, from the Italian word quaranta, meaning forty. Dubrovnik’s authorities based this number on medical theories of the time, which suggested that 40 days was long enough to ensure that no symptoms of the plague would appear if someone had been exposed.

The city’s leaders recognized that disease control was essential both for survival of their citizens and for maintaining the trust of trading partners. Dubrovnik’s model was eventually studied and adopted by other port cities across Europe. But it was here, centuries ago, that the foundation of organized disease prevention through isolation was laid, long before modern medicine took root. The system helped the city survive multiple waves of plague and strengthened its reputation as one of the most forward-thinking ports of its time.

Lazareti

As Dubrovnik’s maritime importance grew and international trade intensified, the simple island-based quarantine system was no longer sufficient. The city needed a more practical and scalable solution. This is why they built Lazareti (the Lazarettos), a fortified quarantine complex built outside the eastern city gates, in the area of Ploče. In this way the city could keep a close eye on incoming travelers and goods.

Construction began in the late 16th century and continued for several decades, with the full complex completed in the mid-17th century. This well-organized facility was made up of ten long stone halls and five inner courtyards. Thick walls surrounded the entire area, which created a clear boundary between those inside and the healthy city beyond. This design minimized the risk of disease transmission while it also allowed for movement, air circulation, and inspection.

Travelers arriving from areas with known outbreaks were brought to the Lazarettos and assigned to specific halls based on the perceived level of risk. Goods, especially textiles, food, and wooden items, were also quarantined. Often, cargo would be aired out, washed, or fumigated to ensure no diseases were brought in by contaminated items. Each building had a specific function. They had sleeping quarters, storage spaces, guard posts, and even facilities for medical personnel.

The Lazarettos had their own fresh water supply, latrines, and drainage systems. This helped prevent disease outbreaks within the quarantine itself and allowed those housed there to remain relatively comfortable and safe during their isolation.

Over the centuries, the Lazarettos served as Dubrovnik’s first line of defense during numerous epidemics. The system proved highly effective, which earned the city international recognition for its structured and humane approach to quarantine. Even at a time when fear of plague often led to violent practices elsewhere, Dubrovnik remained rational and organized in its response.

How Dubrovnik quarantine worked in practice?

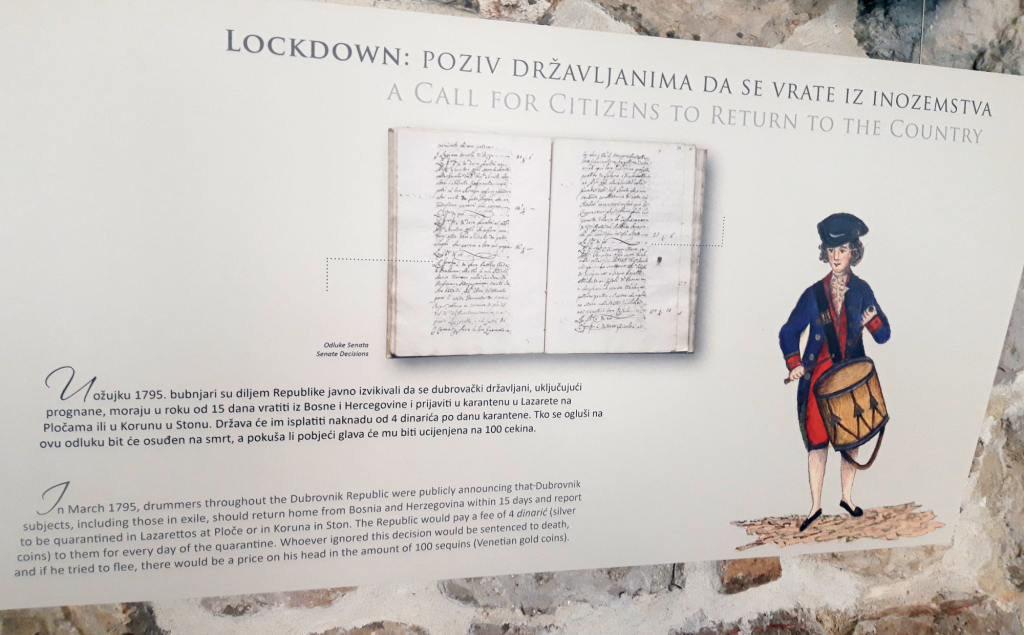

When a ship approached Dubrovnik, it was first inspected from a distance. If it arrived from a port known to have recent cases of plague or other contagious illnesses, it was immediately subject to quarantine. The vessel would anchor offshore, and no one was allowed to disembark until further notice. Officials recorded the ship’s origin, cargo, and passenger list. If the origin was deemed risky, all on board were ordered to remain isolated for a specific period. Initially for 30 days, which was later extended to 40.

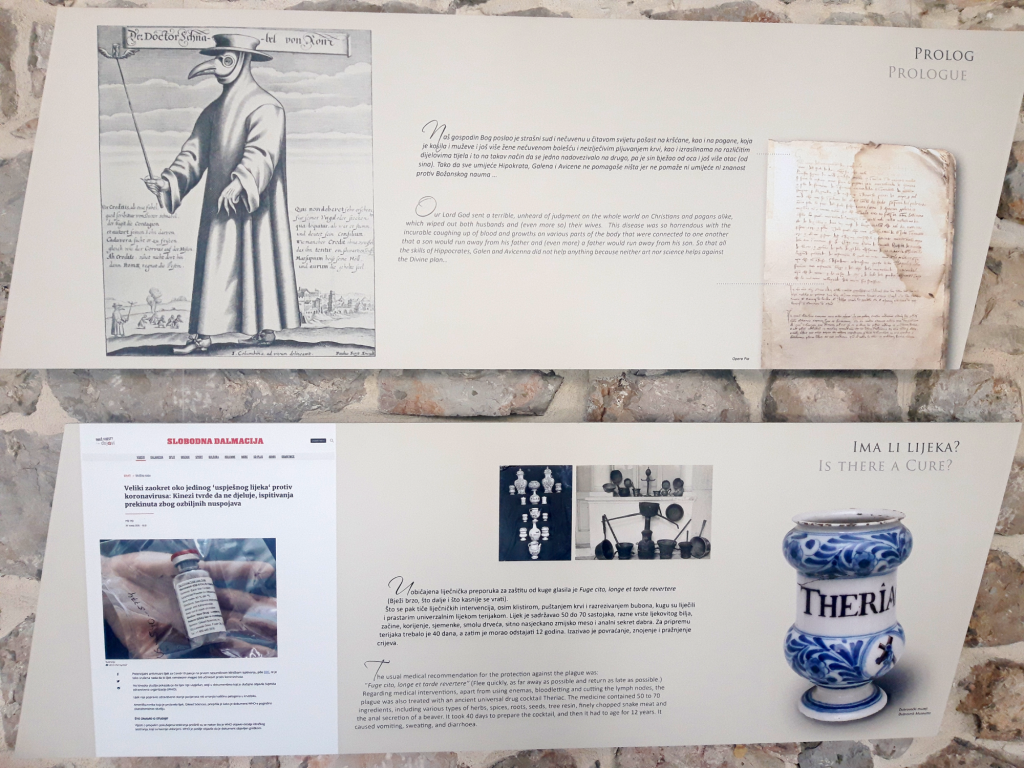

Quarantined individuals were then transferred to designated islands like Mrkan or Bobara, or later, to the Lazarettos complex near the city. There, they stayed in modest accommodations under supervision. Officials enforced strict rules: no physical contact with the city’s residents, regular health inspections, and controlled handling of goods. Merchants’ cargo was often unpacked, fumigated, and left to air out in separate holding areas. In some cases, items were doused in vinegar or exposed to smoke from burning herbs, as these methods were believed to reduce infection risk.

The quarantine process was overseen by a team of health officers known as “knezovi zdravlja” (health counts), as well as guards, port officials, and medical staff. These individuals were highly respected and held to strict ethical and legal standards. Dubrovnik’s regulations punished any evasion or violation of quarantine with heavy fines or imprisonment. This strict enforcement made the system effective and allowed the Republic to avoid many of the devastating outbreaks that paralyzed other cities.

Visit to Lazareti Dubrovnik

If you’re exploring Dubrovnik and looking for something a bit different, the old quarantine sites are worth adding to your itinerary. The main site to check out is Lazareti. What used to be a quarantine station for travelers and goods is now a lively cultural venue. The layout is still mostly intact, and has ten long stone halls with high walls and inner courtyards.

The same halls now host art exhibitions, dance performances, and community workshops. If you’re visiting in the evening, you might even catch live music or a dance performance in one of the courtyards. Performances of local folklore ansamble Linđo are among the most interesting ones.

Visitors can walk through the preserved courtyards and imagine what life must have been like for those held here centuries ago. With views overlooking the old harbor, the location is a powerful reminder of how Dubrovnik’s history of public health innovation helped shape both its past and its identity today.

In 2021, right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, a great exhibition called COVID-19 and the Plague was set up in Dubrovnik’s Lazarettos. It drew some really interesting parallels between how the city dealt with COVID and how it handled the plague centuries ago. As it turns out, the old system was surprisingly smart and forward-thinking.

For those who are more curious about the origins of Dubrovnik’s quarantine policy, there’s the option to visit the islands where the first isolation measures took place, islets Mrkan and Bobara, off the coast near Cavtat. They’re not developed for tourism, so don’t expect facilities or marked trails. But if you’re up for a short boat trip and a bit of walking around ruins, they’re a quiet and interesting side trip. The structures are mostly just foundations and walls now, but the location tells the story.

You can also ask local guides or agencies about custom tours focused on Dubrovnik quarantine history. Some walking tours include the Lazarettos and nearby areas that were part of the old city’s public health system. If you’re already planning to explore the city walls or the eastern entrance, it’s easy to add a quick visit to the Lazarettos.

Healthcare and social welfare in Ragusa

Quarantine wasn’t the only public health effort in Ragusa. The city had a broad, structured approach to medical care and social welfare that reflected its values and its priorities.

One of the earliest public hospitals in the region was the Domus Christi, founded in the mid-14th century. Originally it served as a shelter for the poor, sick, and elderly, and it gradually became a place where medical treatment was provided. It offered care during epidemics, but also treated injuries and chronic illness in daily life. The hospital was funded by the Republic and run with clear rules, including staff regulations and public oversight.

Dubrovnik also became known for its medical professionals. The Republic hired physicians and surgeons on fixed salaries. Many were trained in Italy and other major centers of medicine and came to Ragusa under contract. The city regulated their work, including how they treated patients and how much they could charge. This was unusual for the time and helped ensure care was available to more than just the wealthy.

Pharmacies were another important part of Ragusa’s health system. The pharmacy at the Franciscan Monastery, founded in 1317, is still open today. It’s one of the oldest in Europe still operating in its original space. In medieval times, it was a central hub for preparing herbal remedies and storing imported medicines. It worked closely with physicians and hospitals, and even had written rules about the preparation and distribution of treatments.

The Republic didn’t just care about the sick citizens. They supported foundling homes and orphanages, including the Ospedale della Misericordia (established in 1432), which took in abandoned children. These institutions show how the city protected its most vulnerable in organized ways long before modern systems existed.

Dubrovnik sewage system and water supply

Dubrovnik at that time also had a tightly regulated network of water supply, waste removal, and street-level hygiene. This made it one of the cleanest cities of its time.

At the heart of this system was a sophisticated Dubrovnik sewage network. It was built with stone-lined channels under the streets that used gravity to carry waste out to sea. These channels still exist in parts of the Old Town today. The city enforced cleanliness laws with fines and regular inspections. Residents were not allowed to dump waste carelessly, and cleaners were hired by the city to maintain the streets and drainage.

Even today, parts of the original sewage system remain functional or preserved as historical examples of early urban engineering. While you walk the city, you may notice small stone grates or drainage openings along older buildings. These are the visible traces of an infrastructure designed centuries ago with health and hygiene in mind.

Equally important was the water supply system. In 1436, Dubrovnik built an aqueduct designed by the Neapolitan engineer Onofrio della Cava. It brought fresh water from a spring in the village of Šumet, several kilometers away, into the city. This massive project ended at Onofrio’s Large Fountain near Pile Gate. To the surprise of many visitors, you can still drink clean water from this fountain. On the opposite end of the city, Small Onofrio’s Fountain served the old marketplace and several buildings close by.

Public fountains like these made clean water available to everyone. This helped reduce illness linked to contaminated supplies, and gave the city resilience during sieges or dry seasons. Rainwater collection cisterns were also common, used both in private homes and public buildings.

In addition to waste and water systems, Dubrovnik enforced rules on food safety. Market inspectors checked goods for quality, especially meat and grain. During epidemics, rules became stricter. They would regulate the handling of food, contact between people, and even burial practices. Together, these efforts kept the city livable and its people healthier than many of their European neighbors.

Dubrovnik’s legacy in public health

Public health was a core part of how the city functioned. Quarantine was part of a bigger picture that included clean streets, fresh water, access to medical care, and protection for the vulnerable.

The Lazarettos still stand today as proof of this approach. Structures that once isolated the sick are now open to artists, travelers, and anyone curious about how a city can survive and adapt. Walk the Old Town, and you’re walking above a medieval sewage system.

Fill your bottle at Onofrio’s Fountain, and you’re drinking from a 15th-century aqueduct. Step inside the Franciscan pharmacy, and you’re seeing centuries of healing, still in place. All of these sites are reminders of how a city, through structure and foresight, can care for its people and protect its future.